Chapter 3b - Moving Toward Incorporation

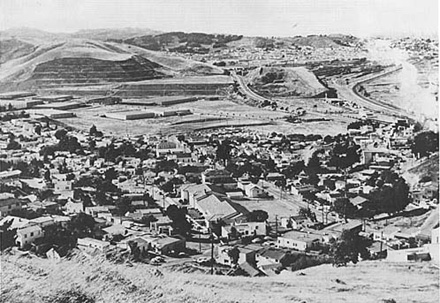

Moving Towards Incorporation

The Desire for Home Rule

As the people of Brisbane lived, worked, and played through the 1950s, they vigorously sought to define and defend their way of life. In this period of transition and development, one can see a community attempting to come to terms with itself and with its future. Ultimately, the people of Brisbane had to confront the issue of home rule. A number of factors were leading many residents to conclude that the town needed to take charge of its own destiny. These compelling factors included such issues as a lack of adequate capital to ensure future growth, the difficulties of obtaining adequate civic services, and the concern that powerful neighbors might dictate Brisbane's future course. Against these concerns, many residents felt another powerful consideration. They were equally concerned that, by incorporating, Brisbane might lose that special quality of rural isolation that so sharply distinguished it from other Bay Area communities.

"Banks outside of Brisbane were reluctant to lend money..."

Many Californians recall the 1950s as a period of unparalleled economic growth and development. As the rejuvenated American economy turned its strength and capital toward domestic projects, many Bay Area communities experienced an explosive growth in housing, public construction, and city services. Indeed, some of this growth did affect the community of Brisbane. Most spectacularly, the state of California began construction of a new Bayshore Freeway in 1954 to take the place of the antiquated two-lane Bayshore Highway. As a resident of Brisbane during that time, Dick Schroeder recalls the impact of the new freeway on the town. "When they put in the freeway, that relieved us of all the traffic. Before, we had more accidents. We even used to have a 'Dead Man's Curve.' People used to pass over the double line and boom, there was a head-on collision. So that new freeway really helped Brisbane." For the most part, however, Brisbane was comparatively untouched by the building boom of the 1950s. "There wasn't too much of a housing boom here," relates Dick Schroeder. "Most of the houses here were built in '38 and '39. During the war, you couldn't get any materials to build a house. And then afterwards, you couldn't get any money. Somehow, the banks didn't want to come in here."

As a resident who came to Brisbane in the mid-1950s, Jay Fichera can expandupon the same theme. "When we were not incorporated, we didn't have a bank here," remembers Fichera. "Banks outside of Brisbane were reluctant to lend money. And if they did, where they could have loaned $50,000, they would loan half that much or less. They were prejudiced. They had thumbs down on Brisbane. That's why Brisbane took so long to develop really. Even after we incorporated, it was quite some time before anybody got a substantial loan to build here in town. I was fortunate. I went out of town to get the money to build my place.

"A lot of people would have liked to come here after the war. It was such a nice place. But we just didn't have the facilities to supply them. There was no money around. People weren't building because they didn't have the money. There was a lot of room, a lot of beautiful empty lots. "We used to have a lot of railroad activity down in the lower part of Brisbane, across the highway. Some of the old timers would turn around, when we got together, and they would kid one another, and they would say, 'Hey, there's no lumber down at the railroad yards anymore. That's why people are not building in Brisbane.' They meant that all the lumber that came out of the freight yards had been taken and used to build homes here. That's a joke. But there is some truth to it."

" One costs you fifty cents...another one costs you a dollar..."

As residents of an unincorporated city, the people of Brisbane also had to struggle for such basic civic services as street paving, police protection, and fire protection.

"When we arrived, some of the streets were still dirt roads and some were cobbled," relates Jay Fichera. "Someone came up with the idea that we should repave San Bruno Avenue because there were ditches and big chuck holes. Some of the elderly people, when the rains came, couldn't cross the street unless they came down to the corner of Visitacion Avenue. So I decided to join a committee and act as its chairman and we got enough votes to pave San Bruno Avenue. To do that, all the people who lived on San Bruno Avenue would have to sign that they would pay an additional taxation for the paving. "Then we tried to buy more police protection from San Mateo County. They wanted everything and wanted to give us nothing. They wanted to come in and circulate around the town maybe once a day, once in the morning, or maybe eight times a week. If anything of an emergency nature was to happen, we would have been at their mercy. We would have had to wait for them to get here whenever they got here. For police protection, that's no good." Dick Schroeder echoes the same concerns regarding the lack of police protection at that time. "The Sheriff of San Mateo sent out two guys to be here all day. But at twelve o'clock, they went home. Of course, most of the trouble starts between twelve and two when there wasn't a sheriff around." In addition, the people of Brisbane had to struggle to keep their own Volunteer Fire Department solvent. "I don't think anybody or any community throughout the entire state of California had a better Volunteer Fire Department than Brisbane," Jay Fichera proudly states. "We did everything. We bought our own trucks. We maintained our own trucks. We built our own trucks. And this was all from people who volunteered their time. We had no paid person in the department. We used to run bake sales to get money to do things. We ran parties. We ran dances. We did everything under the sun to make money and maintain our Fire Department." The entire system for providing social services was complex, cumbersome, and expensive. "We had a fire district, a water district, a police district, and a sewer district," summarizes Dick Schroeder. "All these districts! One costs you fifty cents. Another costs you a dollar. After we got incorporated, all of those districts came within $3.20 of the city. In other words, it would have cost about $6.00 just for the different districts." Thus, as Brisbane stood poised to enter a new decade, the town also was moving towards its greatest act of self-assertion and independence: incorporation.

Incorporation

A Matter of Evolution

On May 2, 1960, a group of citizens called a public meeting to discuss whether or not the people would like to study the feasibility of incorporation. At this meeting, a committee was created to study the issue. The committee consisted of John E. Turner, Fred Schmidt, Louis J. Duncan, and Barbara Pratt. The drive towards incorporation did not spring up in Brisbane on any one day or at any one hour. The first public discussion of the issue goes as far back as the 1930s. Further, as many public documents show, often people referred to the unincorporated status of the town as an explanation for any or all ills.

Incorporation then was more of a matter of evolution than of any one dramatic turn of events. It took time for the majority of Brisbane's residents to come to the view that there was a real need for incorporation. To understand the whole issue, one needs to see the underlying process behind incorporation. To do this, one should look at the issue from the differing perspectives of three active participants: Dick Schroeder, Jay Fichera, and Fred Schmidt.

"They thought they were going to run the town, but they didn't get far..."

As an active participant in the struggle to incorporate, Dick Schroeder describes how the people of Brisbane gradually made up their minds about Brisbane's future course. As Schroeder remembers, the issue of incorporation was considered in the late 1950s and rejected. "Two years before the actual incorporation," he relates, "we tried to incorporate, and lost. People claimed that the state was going to pour something down their throats. The people that were at the head of the incorporation drive said, 'Well, we have to have it by February in order to get the state monies.' But, any time you try to force something down people's throats, they just vote no. "In the first attempt at incorporation, we had all of the Crocker Estate as a part of Brisbane. Crocker wanted us to incorporate, to get away from Daly City. They had a consulting outfit come to promote the deal. Well, they promoted a little bit too much. They said, 'Well, this is the old Brisbane and that's new Brisbane.' Yeah, they thought they were going to run the town, but they didn't get very far. People here in Brisbane figured that they were going to have large buildings in there with smokestacks and stuff like that." Schroeder also remembers how the tide turned in favor of incorporation as the people of Brisbane considered the issue two years later. "It was a matter of educating people to support incorporation," he recalls. "Just by talking to them, and showing them what could be gained, and what we were losing as far as extra taxes and things like that. In addition, the county started talking about Urban Renewal. I went to a meeting of the county supervisors in Redwood City. After the meeting, in the back end of the room, I saw they had all of Brisbane in pictures. They showed how they were going to start Urban Renewal in Brisbane. They had it all figured out how they were going to force Urban Renewal on the whole thing and start all new. Just like they were going to bulldoze everything and start all over.

"They were going to get people's houses and not give them anything for it. They would just wipe things out and give people a little bit for the assessed value. But that didn't amount to anything. It wouldn't have been enough to buy a lot anyplace else. So we went to the next meeting in Redwood City and started complaining right then and there that they had better hold this thing off until we could have a few hearings. "That really cooked the county's goose in a hurry. That was in 1960. That's when the whole thing started for the second incorporation movement. That's when incorporation really got moving in a hurry."

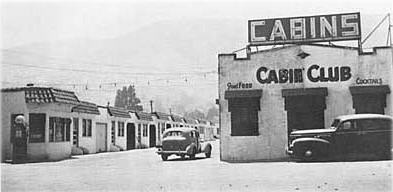

The AutoCourt as it looked in the '40s

"Incorporation, that's a touchy subject..."

As a participant in the struggle for incorporation in the early 1960s, Jay Fichera offers an eyewitness account of some of the complex emotions and attitudes surrounding the issue. In particular, Fichera recalls how relations between the people of Brisbane and both the Crocker Estate and Southern Pacific affected the move to incorporate. "Incorporation, that's a touchy subject," remembers Fichera. "Up until the time we incorporated, the only governing body in the City of Brisbane was the Fire Department. The Fire Department had a three-man commission. I was one of the commissioners. We were the only governing body with any authority. As such, we had our fingers in everything else that happened in town. We tried to keep everything straight and honest. "I wanted incorporation very badly, because I am a firm believer in self- government. But one of the reasons why we kept stalling was my insistence that the Crocker Estate give us more ground, more acreage, more help with a first-class post office, and a bank. I told the Crocker Estate how I felt about these issues at a number of private meetings. Now they didn't see fit to give us more ground. They couldn't help us move from a third-class to a first-class post office. And, even though they had a connection with Crocker National, they said there wasn't enough people and money here in Brisbane to support a bank. Now I can understand that. But they wouldn't even promise us a bank, or promise to look into it in the future, to see whether we deserved a bank after we started developing some of their grounds. "When the Crocker people couldn't promise any of these things, the only solution I had was, 'If you want me to support incorporation, give us the Crocker Estate. All of the grounds.' At the time, they couldn't see fit to do that. So I couldn't see fit to support incorporation.

"I am ready to say that most of the people who opposed incorporation only did so because we were not getting enough from the Crocker Estate. The Crocker Estate would only give us up until the Tunnel Road. That's the boundary line that Crocker was willing to give up and incorporate. I, for one, and several others who are still active in Brisbane, opposed it because we wanted all of the Estate. "A lot of people may not realize it but Southern Pacific has always been a friend of Brisbane. When we incorporated, they were willing not to oppose us or give us any trouble or put any obstacles in our way. They very willingly came in. Now whether some people might have a difference of opinion, well, I don't think they know all the facts. SP has been our friend and still is our friend. "Despite our objections over the Crocker Estate, there was still a very strong movement to incorporate. Two or three groups that were working individually really got together and decided, 'Hey, this is really it.' I can remember Arthur Kennedy, who did quite a bit for this town, was one of the people for incorporation. So he was on the other side of the fence from myself. He said, 'Let's not fight for this or that. We'll get it later.' I said, "No way, we get it now or we'll never get it.' So therefore we were agreeable as far as the town incorporating. Yet we disagreed on what we were looking for in terms of benefits for the town. "To sum it up, I would say that the primary reason for incorporation, or at least the reason why we agreed to incorporate with so much speed at that time, was because we didn't want the supervisors in San Mateo County, or anybody else, to come in here and tell us what to do and how to do it, and to shove it down our throats. I don't think that the people of Brisbane will ever stand for that, from anybody."

"Like any old town you'd read about in the old wild West..."

As a member of the original feasibility committee, Fred Schmidt has a unique perspective on the entire issue. "First, the fire district was formed and a water district was formed. When the water district was formed, they had to buy out the private agencies. That was a big battle. So, that's how the community sort of developed. It developed like any old town you'd see on television or read about in the old wild West, the same deal. "In the late '50s, there was a desire to incorporate the community and try to absorb all these districts so that it was under one control and that improvements could be made in an orderly fashion. It was also done to protect the community. There was a program set up in California called 'Urban Development.' What this meant was that they would take urban areas that had developed poorly because of the efforts of the people to build their own homes in a ramshackle way. Well, a good part of Brisbane was developed by families. It was all home-built stuff. There was some fear that this Urban Development Program would just bulldoze the whole community and start all over again. Well, that fear kind of created in people's minds the thought that we ought to have our own town so we could control it ourselves, so we could keep the rural atmosphere, and not worry about this or worry about that. "On the other hand, incorporation had failed in elections before because the people were a little bit afraid, I think, of what it might cost them -- incorporated communities or towns seemed to cost more than county-controlled systems. Some of the people really didn't want a local government coming up and looking into their affairs. They didn't want the mayor or somebody else telling them what the heck to do. They were happy with the county setup. They thought it would be more rural if it was kept in the county setup.

"When I was on the investigating committee, I wasn't sure that incorporation was proper for the community. In fact, I wasn't for it. Again I was a little bit afraid of the amateur politician. On the other side of the coin, America is made up of amateur politicians. At any rate, after looking into the possibility of being put under the bulldozer, so to speak, I decided that perhaps incorporation would be the right thing to have." After six months of study, the committee recommended that the town vote to incorporate a 2.5 square mile area. In addition, a budget was proposed, along with suggested boundary lines, and future city plans. Finally, a date for an election was set: September 12, 1961. On that date, the residents of Brisbane were asked, "Shall the proposed City of Brisbane become incorporated as a general law city?" The response was overwhelmingly positive. A total of 710 people voted "yes," while only 296 voted "no." The voters also elected their first city council. This body consisted of John E. Turner, Jess Salmon, Ernest Conway, James Williams, and Edward Schwenderlauf. In one bold stroke, the people of Brisbane had voted to incorporate into a city and elected a body of men to help govern them. Under their guidance, Brisbane stood poised at the beginning of a new era in its history.

"It reminds me of a big family..."

As the early history of Brisbane demonstrates, the town has always been marked by a spirit of independence and pride. Bob Lloyd, who has served as a school superintendent in Brisbane, expresses how this spirit of vocal partisanship and pride has extended over the years. "People in Brisbane pride themselves on their independence. They are tremendously independent. There almost seems to be a need to be outspoken. The town has had a history of controversy. There seems to be always a pot stirring somewhere." No matter how bitter the struggle or controversy, Brisbane has maintained the cohesiveness and small-town flavor that goes hand in hand with this spirit of independence. "To know Brisbane, you have to go to one of our meetings," elaborates Dorothy Radoff. "If you really want to see this spirit of independence, they are really good. They are like the old town hall meetings that they had when the nation first started. "Oh, this town has always been fiery about one thing or another. I think it's sort of remarkable in its way. I look back and I think, 'You know these people are really remarkable.' "Some call Brisbane, 'The City That Grew Out Of The Depression.' But many of us call it, 'The City With A Heart.' We've had a lot of dissension here, but to me, it reminds me of a big family. In most big families, the brothers and sisters argue, but when the chips are down, they have a heart."

| Previous Segment |